Up for some British-German insights?

Your cultural pilot: satire on board

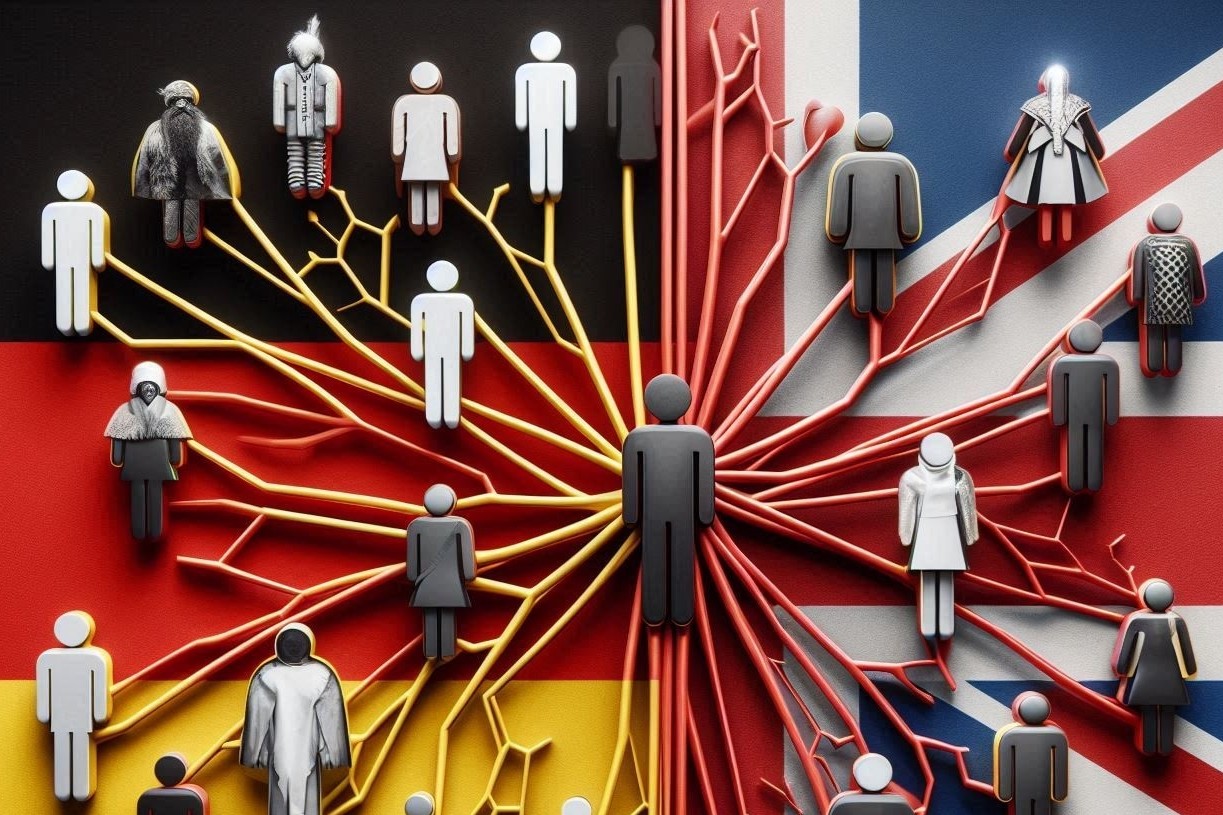

What really happens when British understatement meets German thoroughness? Expect awkward corporate maneuvers, everyday culture clashes, and business models so absurd they just might work. Sharply observed, cheerfully exaggerated — and guaranteed to make you see familiar worlds with fresh eyes.

Tap the pic and let the stories fly!

Collab Charter

A witty exploration of the love-hate dance between Britain and Germany, capturing the delightfully awkward dynamics of corporate life.

Contrasting Pairs

When different cultures meet, contrasts become evident (Contrasting Pairs). They challenge us to question our habitual ways of thinking – and invite us to see diversity not just as something to accept, but as an enrichment and a catalyst for personal growth.

Vision Accord

Boiling the Ocean: Business Models no one asked for